- Singapore is a pro-enforcement jurisdiction, meaning the courts rarely interfere with international arbitration awards unless there is a severe procedural flaw.

- Foreign awards from over 170 signatory countries of the New York Convention are enforceable in Singapore as if they were local High Court judgments.

- Enforcement requires a formal application to the General Division of the High Court, supported by the original award and the arbitration agreement.

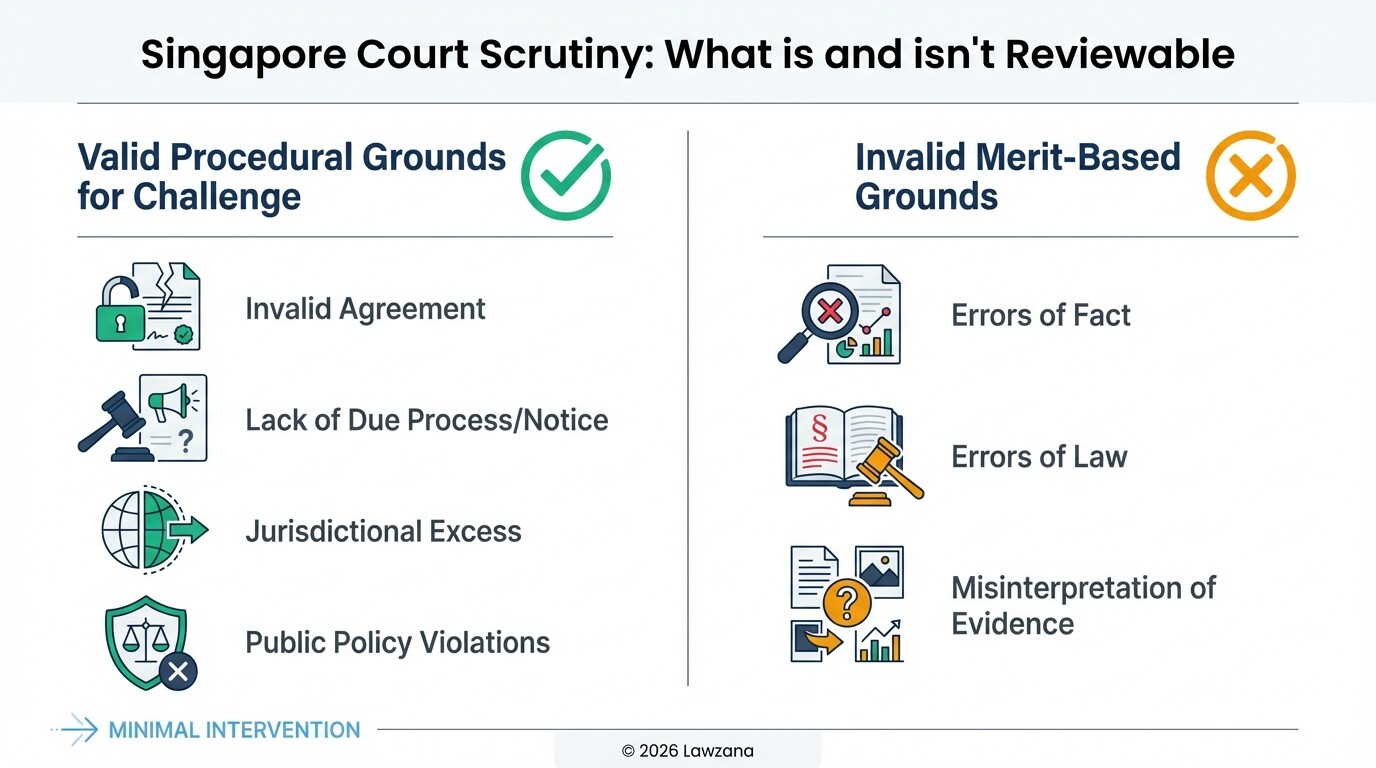

- Grounds for refusal are narrow and do not include errors of fact or law made by the arbitrator.

- Creditors can obtain "freezing orders" (Mareva injunctions) to prevent debtors from moving assets out of Singapore during the enforcement process.

How Do You Enforce an International Arbitration Award in Singapore?

To enforce a foreign arbitral award in Singapore, you must apply for "leave of court" under the International Arbitration Act (IAA). Once the High Court grants this leave, the award is recognized as a court judgment, allowing you to use local enforcement mechanisms like seizing assets or garnishing bank accounts.

The process is governed by the New York Convention, which ensures that awards made in other member states are treated with the same respect as domestic decisions. The application is typically made "ex parte," meaning the debtor is not initially present. You must provide:

- The duly authenticated original award or a certified copy.

- The original arbitration agreement or a certified copy.

- A certified English translation if the documents are in another language.

Once the court grants the order, it must be served on the debtor. The debtor then has a specific window-usually 14 days if served in Singapore-to apply to set the order aside. If they fail to do so, the award becomes fully enforceable.

What Are the Prerequisites for Enforcement Under the New York Convention?

The primary prerequisite is that the award must be "final and binding" and originate from a state that is a signatory to the New York Convention. Singapore courts focus on the validity of the arbitration agreement and whether the dispute falls within the scope of that agreement.

Under Section 29 of the International Arbitration Act, the following must be established:

- Reciprocity: The award must be from a convention country.

- Proper Documentation: Submission of the arbitration agreement and the award is mandatory.

- Legal Capacity: The parties must have had the legal capacity to enter the agreement under the law applicable to them.

- Scope of Dispute: The matters decided in the award must be those that the parties agreed to arbitrate.

Singapore's judiciary takes a "minimal curial intervention" approach. This means the court will not re-examine the merits of the case; it only checks if the basic legal requirements of the New York Convention are met.

What Are the Common Grounds for Challenging an Award in Singapore?

Challenging an award in Singapore is difficult because the courts do not allow appeals based on the arbitrator making a mistake in law or fact. Instead, challenges are limited to "due process" issues, such as a lack of notice or the arbitrator exceeding their authority.

The most common grounds for refusal or setting aside an award include:

- Invalidity of Agreement: The arbitration agreement was not valid under the law the parties chose.

- Inability to Present Case: A party was not given proper notice of the appointment of the arbitrator or the proceedings.

- Excess of Jurisdiction: The award deals with a dispute not contemplated by or not falling within the terms of the submission to arbitration.

- Composition of Tribunal: The tribunal's setup or the procedure followed was not in accordance with the agreement of the parties.

- Public Policy: Enforcing the award would be contrary to the public policy of Singapore (e.g., cases involving fraud, corruption, or bribery).

What Is the Timeline and Expected Cost for Enforcement?

The timeline for enforcing an uncontested award in Singapore is relatively swift, often taking between 3 to 6 months. If the debtor challenges the enforcement, the process can extend to 12 months or longer depending on the complexity of the arguments.

Legal costs vary based on whether the application is contested. While Singapore is a cost-effective hub compared to London or New York, high-stakes international disputes require specialized counsel.

| Phase of Process | Estimated Timeline | Estimated Legal Costs (SGD) |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Filing & Leave of Court | 4-8 Weeks | $10,000 - $20,000 |

| Service on Debtor | 2-4 Weeks | $2,000 - $5,000 |

| Contested Set-Aside Hearing | 4-8 Months | $50,000 - $150,000+ |

| Asset Execution (Seizure) | 2-4 Months | $5,000 - $15,000 |

Note: Costs are estimates and do not include court filing fees or translation costs.

How Do Interim Measures and Freezing Orders Protect Assets?

Singapore courts have the power to issue interim measures, such as Mareva injunctions, to ensure that a debtor does not dissipate assets before the award can be enforced. These orders are critical when there is a high risk that the debtor will move funds to a different jurisdiction to avoid payment.

To obtain a freezing order, the claimant must demonstrate:

- A Good Arguable Case: You have a strong legal claim that is likely to succeed.

- Assets within Jurisdiction: There are tangible assets (bank accounts, real estate, shares) located in Singapore.

- Risk of Dissipation: There is a real risk that the debtor will remove or hide those assets unless the court intervenes.

These orders can be "domestic" (covering assets in Singapore) or "worldwide" (covering assets globally), though worldwide orders are significantly harder to obtain and require a higher threshold of proof.

Recent 2026 Case Law Updates on the Public Policy Exception

As of 2026, Singaporean courts have reinforced that the "public policy" exception is a very high hurdle that is rarely cleared. Recent rulings clarify that a mere error of law, even a serious one, does not violate public policy.

The courts have moved toward a "narrow" interpretation of public policy, focusing on:

- Fundamental Morality: The award must violate the most basic notions of morality and justice in Singapore.

- Illegality: If the underlying contract involved criminal activity that the arbitrator ignored, the court may intervene.

- Natural Justice: A "prejudice" requirement has been solidified; a party must prove that a procedural breach actually changed the outcome of the case to set the award aside.

These updates confirm that Singapore remains one of the safest jurisdictions for creditors seeking to realize the value of their international arbitral awards.

Common Misconceptions About Enforcement

Misconception 1: "I can appeal the award if the arbitrator was wrong."

In Singapore, there is no right of appeal on the merits for international awards. You cannot ask the High Court to change the arbitrator's mind because they misinterpreted a contract or miscalculated damages. The court's role is purely supervisory.

Misconception 2: "Enforcement is automatic once I have the award."

While the New York Convention makes it easier, you still must go through the formal legal process in the Singapore High Court. You cannot simply walk into a bank with an arbitration award and demand the debtor's funds; you need a court order converted into a judgment.

Misconception 3: "If the award is set aside in the home country, it can't be enforced in Singapore."

While a set-aside at the "seat" of arbitration is a strong ground for refusal, Singapore courts have the discretion to enforce an award even if it was annulled elsewhere, although this is rare and involves complex legal arguments.

FAQ

How long do I have to enforce an award in Singapore?

Under the Limitation Act, you generally have 6 years from the date of the breach of the obligation to honor the award to commence enforcement proceedings in Singapore.

Can I recover my legal costs for the enforcement process?

Yes. Singapore follows the "costs follow the event" principle. If you are successful in enforcing the award, the court will typically order the debtor to pay a significant portion of your legal fees and disbursements.

Do I need to hire a Singapore-based lawyer?

Yes. Only lawyers called to the Singapore Bar have the "right of audience" to represent you in the High Court for enforcement proceedings, even if the original arbitration was handled by international counsel.

What happens if the debtor has no assets in Singapore?

If the debtor has no assets in Singapore, enforcing the award there may result in a "paper judgment" only. However, a Singapore judgment can sometimes be used as a basis for enforcement in other Commonwealth jurisdictions via reciprocal enforcement treaties.

When to Hire a Lawyer

Enforcing an award is a technical process where a single procedural error can lead to a set-aside application by the debtor. You should hire a Singapore lawyer if:

- The debtor has significant assets in Singapore (property, bank accounts, or corporate shares).

- You suspect the debtor is attempting to move assets out of the country.

- The award is high-value and likely to be contested on "public policy" or jurisdictional grounds.

- You need to translate foreign legal documents to meet High Court standards.

Next Steps

- Audit Assets: Identify specific assets held by the debtor in Singapore.

- Gather Documents: Secure the original arbitration agreement and the authenticated award.

- Engage Local Counsel: Contact a firm specializing in international arbitration and High Court litigation.

- File for Leave: Submit your ex parte application to the General Division of the High Court to begin the recognition process.