- Foreign investors primarily use three routes to enter the Indian market: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), Foreign Portfolio Investment (FPI), and Alternative Investment Funds (AIF).

- The Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA) regulates all cross-border capital flows, requiring strict adherence to pricing guidelines and reporting timelines.

- Equity instruments issued to foreign investors must be valued using internationally accepted pricing methodologies, typically the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method.

- Exit strategies should be hard-coded into Shareholders' Agreements (SHA), balancing Indian regulatory restrictions on guaranteed returns with the need for liquidity.

- Offshore arbitration remains the preferred dispute resolution mechanism for foreign private equity firms to avoid the lengthy timelines of the Indian judicial system.

Choosing Between FDI, FPI, and AIF Routes for Investment

Foreign investors select their entry route based on their intended level of control, the nature of the target company, and the desired tax treatment. While FDI is the most common path for strategic private equity, the AIF and FPI routes offer specialized advantages for institutional investors and those targeting listed securities.

The Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Route

FDI is the preferred choice for private equity (PE) firms seeking significant stakes and board representation in unlisted Indian companies. Under the FDI policy, investments are categorized into the "Automatic Route," where no prior government approval is needed, and the "Government Route," which requires approval from the relevant ministry for sensitive sectors like defense or print media.

The Foreign Portfolio Investment (FPI) Route

FPI is designed for institutional investors looking to trade in listed securities, corporate bonds, or units of real estate investment trusts. Regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), FPIs are generally limited to holding less than 10% of the total paid-up equity capital of a single company. This route offers higher liquidity and easier entry and exit compared to FDI.

The Alternative Investment Fund (AIF) Route

Foreign investors can also invest as Limited Partners (LPs) in a SEBI-registered AIF. These funds pool domestic and foreign capital to invest in startups, early-stage ventures, or distressed assets. Investing through an AIF often provides a more streamlined regulatory experience, as the fund manager handles the specific compliance requirements with the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

| Feature | FDI Route | FPI Route | AIF Route |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Regulation | FEMA FDI Policy | SEBI (FPI) Regulations | SEBI (AIF) Regulations |

| Control/Influence | High (Strategic) | Low (Portfolio) | Indirect (via Fund) |

| Target Entities | Unlisted & Listed | Listed primarily | Startups/Private Equity |

| Investment Limit | Sector-specific caps | <10% per company | Varies by category |

FEMA Compliance and Valuation Norms for Equity Instruments

The Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA) serves as the legal backbone for all foreign investments in India, ensuring that capital inflows and outflows do not destabilize the national economy. Compliance involves rigorous reporting to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and adhering to strict pricing guidelines to prevent capital flight.

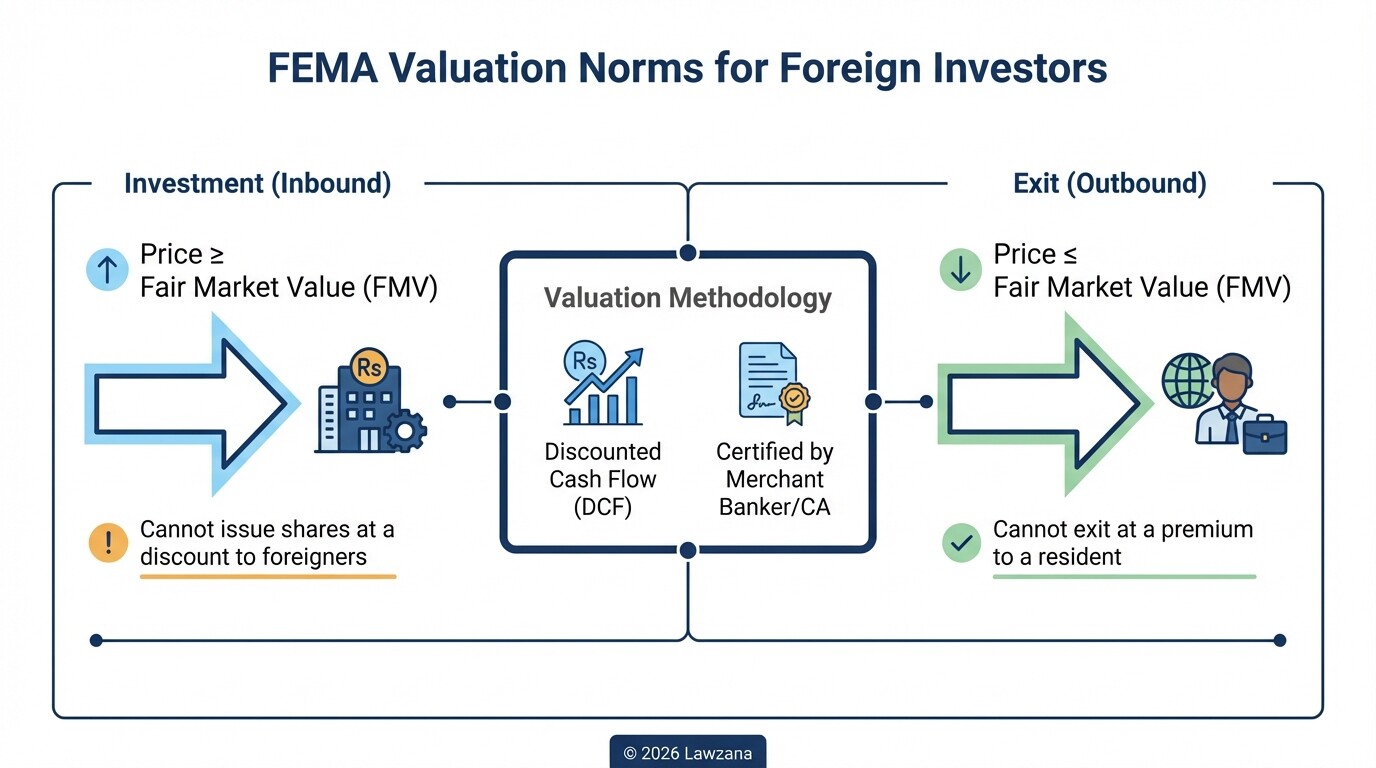

Valuation and Pricing Guidelines

Foreign investors cannot acquire shares in an Indian company at a price lower than the fair market value. Conversely, when selling shares to a resident, the price cannot exceed the fair market value. For unlisted companies, valuation must be performed by a SEBI-registered Merchant Banker or a Chartered Accountant using any internationally accepted pricing methodology, with the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method being the standard practice.

Mandatory Reporting Requirements

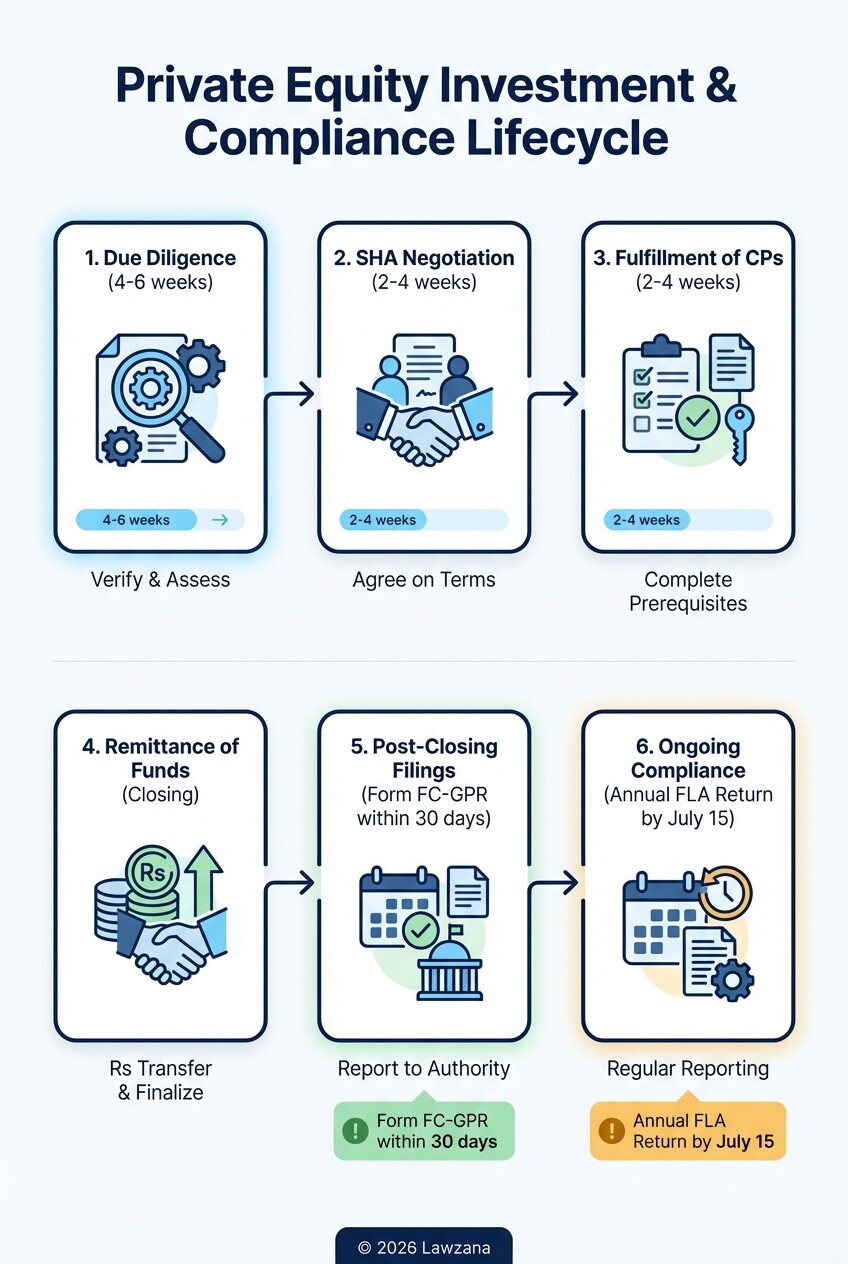

Every foreign investment triggers a series of compliance filings on the FIRMS (Foreign Investment Reporting and Management System) portal. Key filings include:

- Form FC-GPR: Must be filed within 30 days of issuing equity instruments to a foreign investor.

- Form FC-TRS: Required when shares are transferred between a resident and a non-resident.

- Annual Return (FLA): The Foreign Liabilities and Assets return must be submitted by July 15th every year to report all foreign investments held by the company.

Instrument Eligibility

Foreign PE firms can invest in equity shares, fully and mandatorily convertible preference shares (CCPS), and fully and mandatorily convertible debentures (CCDs). Any instrument that is not fully and mandatorily convertible is treated as external commercial borrowing (debt), which is subject to much stricter interest rate caps and end-use restrictions.

Key Clauses in Shareholders' Agreements (SHA) for Foreign VCs

A Shareholders' Agreement (SHA) is the primary document governing the relationship between the foreign investor and the Indian promoters. In the Indian context, these agreements must be drafted with precision to ensure that investor rights are enforceable and do not violate FEMA regulations regarding "guaranteed returns."

Governance and Veto Rights

Investors typically negotiate "Affirmative Voting Rights" or veto rights over critical business decisions. These often include:

- Alteration of the company's capital structure.

- Appointment or removal of key management personnel (KMP).

- Changes to the core business plan or entering new markets.

- Approval of annual budgets and significant capital expenditures.

Exit Rights: Tag-Along and Drag-Along

Because the Indian secondary market for private shares can be illiquid, exit clauses are vital.

- Tag-Along Rights: Protects the minority investor by allowing them to join a sale if the founders sell their stake.

- Drag-Along Rights: Allows the PE investor to force the founders to sell the company if a third-party buyer offers to acquire 100% of the business.

Anti-Dilution and Liquidation Preference

Foreign investors use anti-dilution clauses to protect their stake during "down rounds" (valuation drops in subsequent funding). Liquidation preference ensures that the investor receives their initial investment (plus any agreed-upon multiples) before the promoters receive any proceeds during a sale or winding-up process.

Repatriation of Capital and Tax Implications Under Treaties

Repatriation refers to the ability of a foreign investor to move their profits and capital out of India and back to their home country. While India allows the free repatriation of the sale proceeds of investments (net of taxes), the process must be facilitated through an Authorized Dealer (AD) bank and documented meticulously.

Taxation of Capital Gains

Capital gains tax in India depends on the holding period and the type of instrument.

- Long-Term Capital Gains (LTCG): Generally applies if shares are held for more than 24 months (unlisted) or 12 months (listed).

- Short-Term Capital Gains (STCG): Applies to holdings shorter than the above periods, usually taxed at the investor's applicable slab rate or 15% to 30% depending on the asset class.

Leveraging Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements (DTAA)

India has signed tax treaties with several jurisdictions to prevent investors from being taxed twice. Historically, many PE firms used Mauritius, Singapore, or the Netherlands for their investments. While recent amendments have introduced the "General Anti-Avoidance Rule" (GAAR) and "Principal Purpose Test" (PPT) to prevent tax evasion, these treaties still offer beneficial withholding tax rates on dividends (often 5% to 15%) and specific capital gains exemptions.

Dividend Distribution

Dividends paid by an Indian company to a foreign shareholder are subject to a withholding tax (typically 20% plus applicable surcharges), unless a lower rate is provided under a DTAA. The Indian company must issue a Form 15CA/15CB certificate to the tax department before the bank can process the remittance.

Dispute Resolution: Indian Courts vs. Offshore Arbitration

Resolving legal disputes in India can be a decades-long process due to judicial backlog. For foreign private equity investors, the choice of dispute resolution mechanism is a critical risk-mitigation strategy, often favoring international arbitration over domestic litigation.

Why Offshore Arbitration?

Most foreign investors insist on "Offshore Arbitration" in neutral seats like Singapore (SIAC), London (LCIA), or Hong Kong (HKIAC). The primary benefits include:

- Speed: Arbitration awards are typically rendered within 12 to 18 months.

- Expertise: Arbitrators are often specialists in commercial law, unlike generalist judges.

- Enforceability: India is a signatory to the New York Convention, meaning foreign arbitral awards are generally enforceable in Indian courts with limited grounds for challenge.

The Rise of Domestic Institutional Arbitration

The Indian government has promoted the Mumbai Centre for International Arbitration (MCIA) and the Delhi International Arbitration Centre (DIAC) to provide efficient domestic alternatives. For smaller investments or cases where all assets are strictly in India, domestic institutional arbitration is increasingly seen as a viable, cost-effective option.

Choice of Law

While the seat of arbitration can be offshore, the underlying contract is almost always governed by Indian law if the target company is incorporated in India. This ensures that the rights being enforced do not conflict with mandatory Indian statutes like the Companies Act or FEMA.

Common Misconceptions About Private Equity in India

Myth 1: "100% FDI is allowed in all sectors."

Reality: While India has liberalized most sectors (e.g., IT, manufacturing), several industries have "caps" or "performance conditions." For example, Multi-Brand Retail Trading and Print Media have strict ownership limits and require prior government approval.

Myth 2: "Investors can get a guaranteed exit price."

Reality: FEMA specifically prohibits "assured exit prices" or "guaranteed returns." Any exit price must be based on the fair market value at the time of the transfer. Clauses promising a fixed internal rate of return (IRR) can be legally precarious and may be viewed as debt rather than equity by the RBI.

Myth 3: "The Registrar of Companies (ROC) is the only regulator."

Reality: PE investments are subject to a "triple-regulator" framework: the ROC for company law, the RBI for foreign exchange, and SEBI for securities law (if listed or using an AIF). Missing a filing with even one can lead to heavy compounding fees and legal penalties.

FAQ

How long does it take to complete a PE investment in India?

A typical transaction takes between 3 to 6 months. This includes 4 to 6 weeks for due diligence, 2 to 4 weeks for drafting and negotiating the SHA, and another 2 to 4 weeks for fulfillment of "Conditions Precedent" (CPs) and the final injection of funds.

What is the minimum investment amount for foreign PE?

Under the FDI route, there is no universal minimum investment amount specified by law. However, for certain sectors like "Construction Development," specific minimum capitalization requirements may apply. For AIFs, a foreign investor must typically commit a minimum of INR 10,000,000 (approximately $120,000 USD).

Can foreign investors buy debt instruments in India?

Yes, but they must follow the External Commercial Borrowings (ECB) framework. This includes limits on interest rates (spread over a benchmark), minimum maturity periods (usually 3 years), and restrictions on how the money can be used (e.g., it cannot be used for real estate or stock market speculation).

Do I need a local bank account to invest in India?

No, FDI can be remitted directly from the investor's overseas bank account to the Indian company's account. However, FPIs and AIFs generally require a local "custodian" and a specialized account (NRO/NRE) to manage trades and repatriate funds.

When to Hire a Lawyer

Navigating the Indian regulatory landscape requires professional legal counsel at every stage of the investment lifecycle. You should engage a specialized Indian corporate lawyer when:

- Conducting legal due diligence on a target company to identify hidden liabilities or non-compliance.

- Structuring the investment to ensure optimal tax efficiency and compliance with the latest FEMA updates.

- Negotiating the Shareholders' Agreement to protect your governance and exit rights.

- Drafting and filing the mandatory FC-GPR or FC-TRS forms with the RBI.

- Handling a dispute or enforcing an arbitral award against a local promoter.

Next Steps

- Perform Preliminary Due Diligence: Before signing a Term Sheet, conduct a high-level review of the target's compliance history and sector-specific FDI limits.

- Draft a Comprehensive Term Sheet: Clearly outline the valuation, board seats, and exit expectations to avoid friction during the definitive documentation phase.

- Engage an Authorized Dealer (AD) Bank: Identify a reputable Indian bank to handle the foreign exchange remittances and help navigate the FIRMS portal reporting.

- Finalize the SHA and Articles of Association (AOA): Ensure that the protective provisions in your SHA are also mirrored in the company's AOA to make them binding under the Companies Act.