Table of Contents

- Introduction: Understanding Turkish Child Custody Laws

- The Golden Rule: The "Best Interests of the Child" Principle

- The Legal Foundation: Turkish Civil Code and International Law

- Types of Custody Arrangements in Turkey

- Sole Custody (Tek Başına Velayet)

- Joint Custody (Ortak Velayet)

- Custody for Unmarried Parents

- The Court Process and the Social Investigation Report

- Financial Considerations: How Child Support Is Determined

- International Custody: Relocation and Abduction

- Relocating Abroad with a Child

- International Child Abduction and the Hague Convention

- Modifying a Custody Order

Navigating a child custody dispute is one of the most challenging experiences a parent can face. When this happens in a foreign country, the stress can be compounded by an unfamiliar legal system. In Turkey, the laws governing child custody (velayet) are built on a modern legal code but are also deeply influenced by judicial tradition and evolving international standards. Understanding these laws is the first step toward protecting your parental rights and ensuring your child's well-being.

This comprehensive guide, based on an in-depth analysis of Turkish family law, will walk you through everything you need to know about how child custody is decided in Turkey, from the core legal principles to the practical steps of the court process.

The Golden Rule and The "Best Interests of the Child"

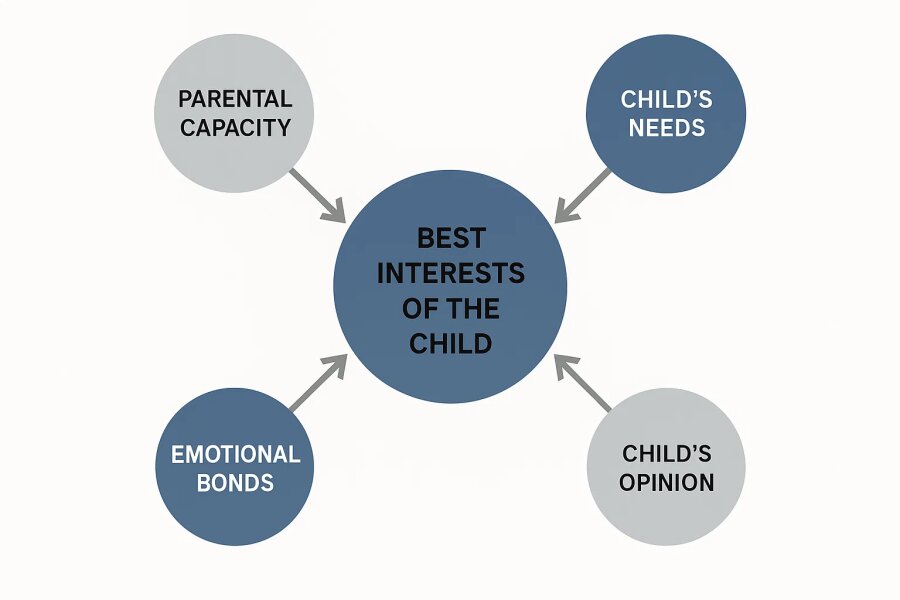

Before delving into any specific rule or procedure, it is crucial to understand the single most important principle that governs every custody decision in Turkey: the best interests of the child (çocuğun üstün yararı). This is the supreme and paramount consideration that a Family Court judge must prioritize above all else, including the wishes of the parents.

This principle is considered a matter of public policy, which means the judge has an active duty to investigate what is best for the child, regardless of what the parents have requested or even agreed upon. This transforms the judge from a passive referee into an active protector of the child's welfare.

To determine what is in a child's best interests, the judge undertakes a holistic evaluation, scrutinizing a wide range of factors, including:

- Parental Capacity: The court will examine each parent's financial stability, profession, housing situation, and overall ability to provide a stable and nurturing home.

- The Child's Needs: The child's specific age, health, educational requirements, and social environment are central to the inquiry. The court aims to minimize disruption and maintain continuity in the child's life where possible.

- Emotional Bonds: The strength of the relationship and emotional attachment between the child and each parent is a critical factor.

- Parental Cooperation: A parent’s willingness to foster a healthy relationship between the child and the other parent is viewed very favorably. Obstructing access or attempting to alienate the child from the other parent can seriously harm a custody claim.

- The Child's Own Opinion: Turkish courts are obligated to listen to and consider the preference of a child who has reached a sufficient level of maturity. While there is no strict age cutoff, the opinions of children aged 12 and above are given significant weight, and children as young as 8 may also be heard. However, the child's wish is not the absolute deciding factor; it is one piece of evidence the judge will weigh among all others.

The Legal Foundation, Turkish Civil Code, and International Law

The primary domestic law governing custody is the Turkish Civil Code (TCC), Law No. 4721. The core rules are found in Articles 335 through 351, which outline the rights and responsibilities of parents. The official text of the law is maintained on government portals like mevzuat.gov.tr, ensuring public access.

However, Turkey's legal system is not an island. The country is a signatory to major international treaties, most notably the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). Under the Turkish Constitution, these duly ratified international agreements on fundamental rights have the force of national law and, critically, prevail over any conflicting domestic statutes. This means Turkish judges interpret the Civil Code through the lens of international standards, a practice that has led to significant evolution in family law.

Types of Custody Arrangements in Turkey

Based on these legal principles, Turkish courts can order different types of custody arrangements.

Sole Custody (Tek Başına Velayet)

This is the traditional and, in contested cases, by far the most common outcome.

- What it means: One parent is granted the exclusive authority to make all significant decisions regarding the child's life, including their education, healthcare, and place of residence.

- The Non-Custodial Parent: This parent retains their parental status and has two primary rights: the right to maintain personal contact through a court-ordered visitation schedule and the obligation to provide financial child support.

- Maternal Preference for Young Children: While the law is gender-neutral, there is a long-standing judicial tendency to award custody of very young children (often under age 7) to the mother, based on the view that they have a greater need for maternal care. This is a strong presumption, but it is not an absolute rule and can be rebutted if the father can prove that granting him custody is better for the child.

Joint Custody (Ortak Velayet)

Joint custody, where both parents share legal decision-making authority after divorce, is a relatively new and evolving concept in Turkey.

Legal Basis:

The Turkish Civil Code does not explicitly mention or regulate joint custody for divorced parents. For years, courts viewed this silence as a prohibition. However, influenced by international conventions, the highest courts have reversed this stance, ruling that joint custody is not against Turkish public policy and can be granted if it serves the child's best interests.

When is it granted?

Joint custody remains rare and is not the default. It is almost exclusively granted in amicable, uncontested divorces where both parents mutually agree to it in a formal protocol and, most importantly, can prove to the judge that they can cooperate and communicate effectively for their child's benefit.

Custody for Unmarried Parents

The law is unambiguous for children born outside of marriage. Under TCC Article 337, custody automatically belongs to the mother. A father who wishes to gain custody must first legally establish paternity and then file a separate lawsuit, where he must prove that transferring custody to him is definitively in the child's best interests.

The Court Process and How a Custody Decision Is Made

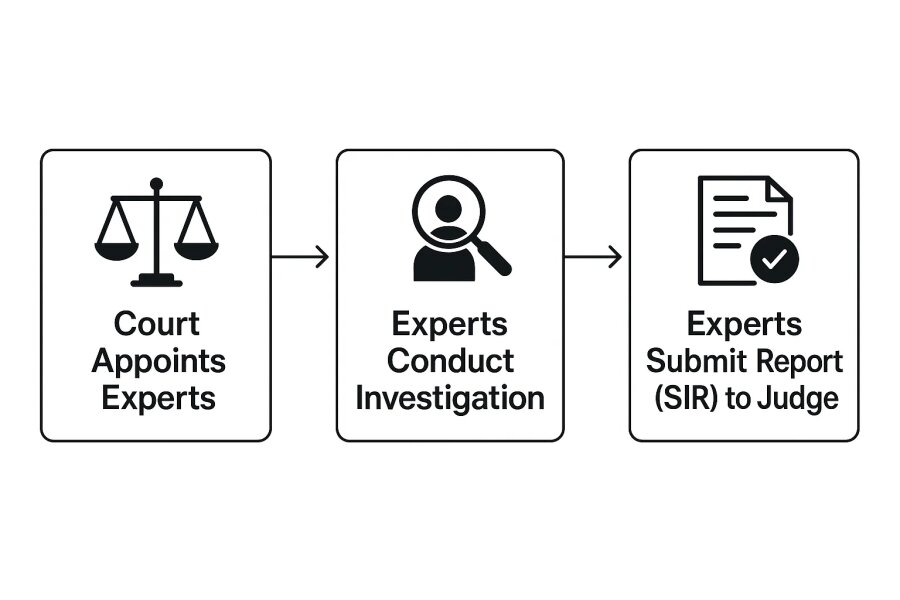

Custody cases are handled by specialized Family Courts (Aile Mahkemesi). Because the judge must actively investigate the child's best interests, the court process relies heavily on outside expertise.

The most critical part of any contested custody case is the Social Investigation Report (SIR). The judge will appoint a panel of experts, typically a psychologist, a pedagogue (child development specialist), and a social worker, to conduct a thorough investigation. These experts will:

- Conduct detailed interviews with both parents and the child.

- Make home visits to observe the living conditions.

- Assess the family dynamics and each parent's capacity for care.

The final report submitted by these experts is profoundly influential. While not legally binding, its recommendations on which parent should have custody carry immense weight with the judge and can often be the turning point in a case.

The Financial Side and How Child Support Is Determined

The non-custodial parent has a legal duty to contribute financially to the child's upbringing through child support, known as iştirak nafakası. One of the most important things for international clients to understand is that Turkey has no fixed formula or mandatory percentage of income for calculating child support.

The amount is left entirely to the judge's discretion. The judge performs a balancing act, considering factors like:

- The child’s actual needs (education, health, lifestyle).

- The financial status and income of the custodial parent.

- The financial capacity and ability to pay of the non-custodial parent.

Child support payments typically continue until the child turns 18. However, if the child continues their education (e.g., university), they can file a new lawsuit to have the support continue until their studies are complete. To protect against inflation, court orders almost always include a clause for an automatic annual increase tied to the official national inflation rate.

International Custody, Relocation, and Abduction

For expatriate families, cross-border issues are a major concern.

Relocating Abroad: A parent with sole custody in Turkey does not have the right to unilaterally move abroad with the child. Doing so would infringe on the other parent's visitation rights. To relocate internationally, the custodial parent must obtain either the other parent's explicit, notarized consent or a specific court order permitting the move.

International Child Abduction: Turkey is a signatory to the 1980 Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction. This treaty is the primary legal mechanism for securing the prompt return of a child wrongfully removed from their country of habitual residence. If a parent takes a child from Turkey to another member country without consent or a court order, the left-behind parent can file a Hague application for the child’s return. However, official reports note that these cases can face significant delays in the Turkish legal system.

Can a Custody Order Be Changed?

A custody decision is never set in stone. The law recognizes that circumstances change, and an order can be modified through a new lawsuit. The parent requesting the change must prove that there has been a significant change in circumstances and that the current arrangement is no longer in the child's best interests.

For Legal Professionals: The developing character of Turkish family law, notably the court recognition of shared custody and the direct application of international treaties, poses both obstacles and possibilities. Staying abreast of the latest Court of Cassation precedents is vital to delivering efficient representation. Lawzana provides a platform for legal professionals to demonstrate their skills, engage with a worldwide network, obtain crucial insights into complicated legal environments, and connect with new clients. Join Lawzana’s network and register your firm now to enhance your business and reach active clients seeking your particular talents.

For Parents Seeking Legal Assistance: Navigating a child custody dispute in Turkey is a complicated road where the stakes are exceedingly high. The appropriate legal assistance is something that is necessary, a requirement to defend your rights and your child's future. Lawzana is a reliable resource to help you understand the law and contact skilled legal practitioners in your region. Explore Lawzana to locate the ideal Turkish family lawyer who can advise you through this essential step.