- In Canada, "nonprofit," "nonprofit corporation," and "registered charity" are not the same thing - your tax status with the CRA is separate from your legal form under federal or provincial law.

- You usually incorporate first (federal or provincial) with articles and bylaws, then decide whether to apply to the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) for charitable registration.

- Registered charities can issue official donation receipts and must file an annual T3010 return with the CRA within 6 months of fiscal year end.

- Boards should be mostly "arm's length" directors and must follow clear governance and conflict‑of‑interest rules to protect the organization and its reputation.

- Using a lawyer early to draft purposes, bylaws, and policies often costs less than fixing problems later or responding to a CRA review.

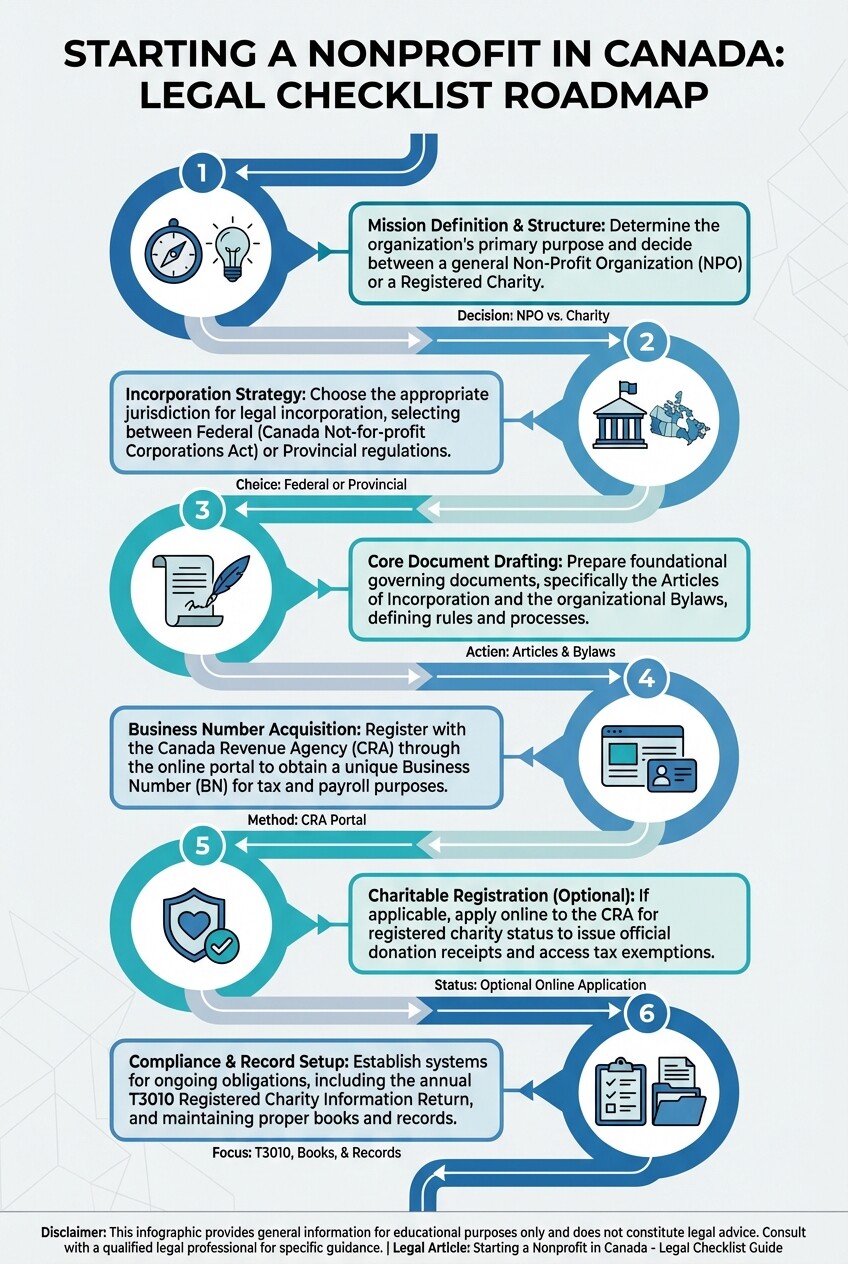

What legal steps are required to start a nonprofit organization in Canada?

To start a compliant nonprofit in Canada, you typically choose your structure, incorporate federally or provincially, obtain a business number, decide whether to register as a charity, and then set up governance and reporting systems. Each step has specific legal documents and deadlines, especially if you seek charitable status with the CRA.

At a high level, most founders will: (1) clarify mission and decide whether they need charitable registration, (2) choose federal vs provincial/territorial incorporation, (3) prepare and file articles and bylaws, (4) get a CRA business like number and any needed program accounts, (5) if applicable, complete the CRA's online charity registration application, and (6) put in place board, finance, and conflict‑of‑interest policies. These early decisions affect your fundraising options, compliance workload, and director liability for years.

- How do I decide between federal and provincial incorporation?

- Can I operate as an unincorporated community group instead of incorporating?

- What ongoing filings do small nonprofits actually have to make?

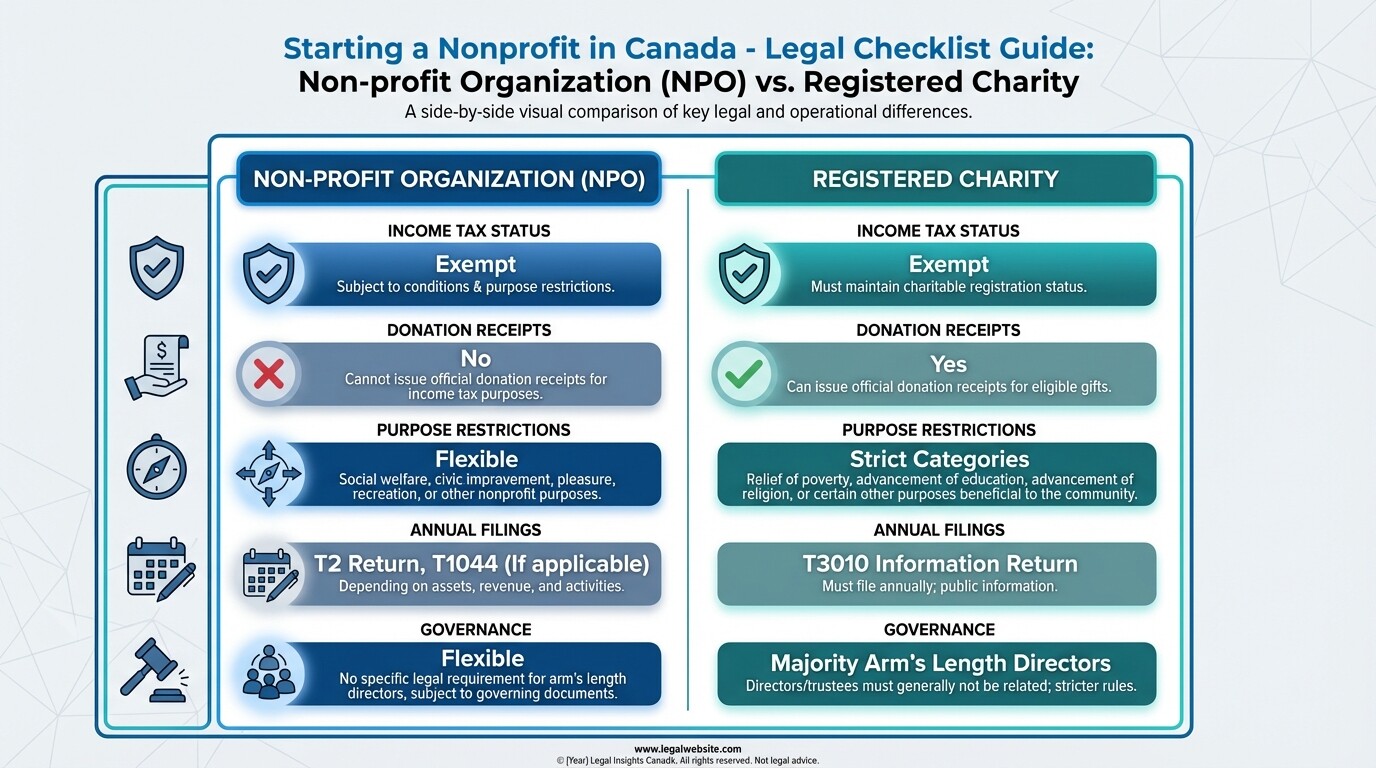

How should you choose between a nonprofit corporation and registered charity status in Canada?

You choose between being "just" a nonprofit (often a non‑profit organization for tax purposes) and becoming a registered charity based on your activities and fundraising plans. Incorporation creates a legal entity; charitable registration with the CRA creates a specific tax status with strict rules and privileges.

There are three key concepts to separate:

- Legal form: You can operate as an unincorporated association or incorporate under a federal or provincial/territorial not‑for‑profit statute, such as the Canada Not-for-profit Corporations Act (CNCA). Incorporation usually provides limited liability, continuity, and better access to grants and contracts. (ised-isde.canada.ca)

- Jurisdiction: Federal incorporation gives broader name protection and may be helpful if you operate in multiple provinces. Provincial statutes (for example, Ontario's Not-for-Profit Corporations Act or Saskatchewan's Non‑profit Corporations Act) are often the default for community‑based organizations. (ised-isde.canada.ca)

- Tax status:

- Non‑profit organization (NPO): An entity that meets CRA's conditions may be exempt from income tax but cannot issue official donation receipts.

- Registered charity: Recognized by the CRA under the Income Tax Act; can issue official donation receipts, may be eligible for more grants, but is subject to tight limits on purposes, activities, political work, and spending.

If your work clearly fits one of the recognized categories of charity (relief of poverty, advancement of education, advancement of religion, or other purposes beneficial to the community) and you plan to rely heavily on donations and grants, applying for charitable status is often worthwhile. If your revenue will be mainly fees, contracts, or government funding, and you want more operational flexibility, remaining an NPO without charitable registration may be better.

- Can my nonprofit start as an NPO and apply for charitable status later?

- What kinds of activities disqualify an organization from charitable registration?

What incorporation documents and bylaws do Canadian nonprofits need?

To incorporate a nonprofit in Canada, you generally need a unique name, articles of incorporation with clear purposes and asset‑distribution clauses, a registered office address, a list of initial directors, and bylaws that govern how the organization operates. Federal incorporation is handled by Corporations Canada, while each province and territory has its own corporate registry and forms. (ised-isde.canada.ca)

Typical core documents include:

- Corporate name and NUANS search (if required): To confirm your name is available, especially for federal incorporation.

- Articles of incorporation:

- Exact legal name

- Statement of purposes/objects (critical if you will seek charitable status)

- Any restrictions on activities or powers

- Membership structure (classes, if any)

- Number or minimum/maximum of directors

- Dissolution clause stating that remaining assets will go to another qualified nonprofit/charity

- Registered office and first directors: Names and addresses of the initial directors and the official address where legal documents can be served.

- Bylaws: The internal rulebook, typically covering:

- Membership criteria, rights, and termination

- How meetings of members and directors are called, quorum, and voting rules

- Board composition, officer roles, and terms of office

- Conflict‑‐of‑interest and indemnification provisions

- Banking and signing authority

- Process to amend bylaws and articles

If you intend to apply for charitable status, it is very important that your stated purposes and dissolution clause match CRA expectations. The CRA publishes guidance on acceptable charitable purposes and expects you to submit final, certified governing documents with your application, not drafts. (canada.ca)

- Should we include multiple classes of members in our bylaws?

- What wording does the CRA expect for charitable purposes and dissolution clauses?

How do you register as a charity with the CRA and what are your ongoing reporting duties?

To register as a charity, you must apply online through the CRA's My Business Account portal, submit your governing documents and detailed descriptions of activities, and wait for the CRA's review. Once registered, you must file a T3010 Registered Charity Information Return every year within six months of your fiscal year‑end and comply with various operational rules. (canada.ca)

Key steps to apply for charitable status:

- Incorporate or organize: Most applicants incorporate first, but trusts and unincorporated associations can sometimes qualify.

- Create a CRA business number (BN): If you do not already have one for payroll or GST/HST, you will obtain one when you register as a charity.

- Sign up for My Business Account: The online charity application is now integrated into this portal. (canada.ca)

- Complete the online application:

- Upload certified governing documents

- Provide detailed descriptions of each program and how it achieves your charitable purposes

- Provide a proposed budget and financial projections

- List all directors, with required personal details

- Respond to CRA questions: The CRA may request clarifications before approving or refusing registration.

There is currently no application fee to become a registered charity, although you will have paid incorporation fees to your corporate registry. The CRA aims to provide an initial response within several months of receiving a complete application, but timelines vary. (canada.ca)

Ongoing charity compliance includes:

- Annual T3010 filing: File online or by mail within six months of fiscal year‑end; late or missing filings can lead to penalties or revocation. (canada.ca)

- Maintaining books and records in Canada: Including minutes, governing documents, financial records, and donation receipts.

- Issuing donation receipts correctly: Following CRA rules for content, timing, and valuation of non‑cash gifts.

- Meeting your disbursement quota: Spending a minimum amount each year on charitable activities or gifts to qualified donees.

Non‑charitable NPOs may still have to file certain returns (such as T2 or T1044) and should confirm their status with an accountant or lawyer, particularly if they earn investment or business income.

- Can we start operating while our charity application is pending?

- What happens if we file the T3010 late or make a mistake?

What board governance and conflict‑of‑interest rules should Canadian nonprofits follow?

Canadian nonprofits should have a competent, mostly arm's‑length board that meets regularly, keeps minutes, and follows clear conflict‑of‑interest procedures. For charities, the CRA expects a minimum of three directors and generally a majority who are not related or otherwise in close business relationships. (canada.ca)

Core governance practices include:

- Board composition:

- At least three directors; many organizations choose 5 to 9.

- Majority at arm's length (not related by blood, marriage, or common business interest), especially for charities.

- Clear officer roles (chair, treasurer, secretary) with written job descriptions.

- Meetings and minutes:

- Regular board meetings with circulated agendas and background materials.

- Minutes that record decisions, key discussions, and any director abstentions due to conflicts.

- Financial oversight:

- Budget approval and monitoring by the board.

- Appropriate level of financial review (compilation, review, or audit) based on your statute and revenue.

- Conflict‑of‑interest policy:

- Requires directors and senior staff to disclose any personal or financial interest in a matter.

- Requires conflicted individuals to leave the room and abstain from voting.

- Documents all disclosures and abstentions in the minutes.

- Can family members sit on the same nonprofit board in Canada?

- Do we need a formal audit, or is a review engagement enough?

Why should Canadian nonprofits involve legal counsel early?

Canadian nonprofits benefit from legal help early because errors in purposes, bylaws, or governance are much harder and more expensive to fix once you are operating or applying for charitable status. A lawyer who understands charity and nonprofit law can design your structure to match your mission, funding model, and risk profile.

Legal counsel can help you:

- Draft charitable purposes that the CRA is likely to accept and that match your planned activities.

- Choose between federal and provincial incorporation and understand director duties under the applicable statute.

- Design bylaws that prevent deadlocks, protect minority members, and support good governance.

- Set up compliant donation receipting, fundraising practices, and grant agreements.

- Prepare for CRA questions during registration or an audit and respond effectively if issues arise.

- Is it worth paying a lawyer if our nonprofit is very small?

- Can a lawyer also help with grant agreements and HR issues?

What are common misconceptions about starting a nonprofit in Canada?

Many founders begin with assumptions that can lead to serious compliance problems. Clearing up these misunderstandings early will save time, money, and stress.

- "Incorporation automatically makes us a charity." Incorporation and charitable registration are separate. You must apply to the CRA and be approved before issuing official donation receipts.

- "We are small, so the rules do not really apply." Even tiny charities must file T3010 returns, keep records, and comply with CRA rules; failure to do so can lead to revocation. (canada.ca)

- "We can just copy another group's bylaws." Bylaws must fit your statute, your membership, and your governance needs; copying without understanding often creates contradictions or illegal provisions.

Frequently asked questions about starting a nonprofit in Canada

How long does it take to get charitable status in Canada?

The CRA's initial review of a complete application often takes several months, and it can take longer if the CRA requests clarifications or if your purposes or activities are complex. You should plan for a total timeline of 6 to 12 months from submission to decision, although simple, well‑prepared applications may be processed more quickly. (canada.ca)

How much does it cost to start a nonprofit in Canada?

Incorporation fees vary by jurisdiction but are often in the range of about CAD 75 to CAD 400 provincially and around CAD 250 federally, plus any name‑search fees. Legal and accounting support, if you choose to use it, is usually the larger cost; CRA does not currently charge an application fee to become a registered charity. (ised-isde.canada.ca)

Can a Canadian nonprofit pay its directors or founders?

Nonprofits and even charities can sometimes pay directors or founders for services, but strict rules apply, and the arrangement must be reasonable, clearly documented, and in the organization's best interests. The CRA scrutinizes payments to directors of charities closely, so you should get legal advice before entering into paid relationships with board members.

Do we need a lawyer to file the charity application with the CRA?

You are not required to use a lawyer, and many groups prepare and submit their own applications using CRA guidance and checklists. However, legal review is particularly helpful if your structure is unusual, your activities are novel, or you have already received questions or a draft refusal from the CRA. (canada.ca)

Can we operate across Canada if we incorporate provincially?

Yes, but you may need to register extra‑provincially in other provinces or territories where you carry on activities, and your name protection is narrower than with federal incorporation. If you expect to grow nationally, federal incorporation may be more efficient in the long term. (ised-isde.canada.ca)

When should you hire a lawyer to start a Canadian nonprofit?

You should strongly consider hiring a lawyer as soon as you have a clear mission and are ready to choose your structure, rather than after you have already filed documents. This timing allows counsel to shape your purposes, bylaws, and governance model in ways that line up with CRA expectations and your chosen statute.

Legal help is especially important if you plan to apply for charitable status, expect to operate in more than one province, anticipate significant fundraising, or will hold real estate or employ staff. A lawyer can also coordinate with an accountant to ensure your financial systems, receipting practices, and reporting processes are set up correctly from day one.

What are your next legal steps to start a Canadian nonprofit?

To move forward, start by writing down your mission, target beneficiaries, and main activities, then decide whether you are aiming to become a registered charity or to remain an NPO. With that decision made, choose federal or provincial incorporation and draft articles and bylaws that reflect both your mission and the legal requirements in your jurisdiction, using official guidance such as Corporations Canada's "Creating a not‑for‑profit corporation" and the CRA's resources on charitable registration. (ised-isde.canada.ca)

Once incorporated, obtain your business number, apply for charitable status if appropriate, and implement board, financial, and conflict‑of‑interest policies. If possible, engage a Canadian nonprofit or charity lawyer through a platform like Lawzana before you file with the CRA, so you can address potential issues early and launch your organization on a solid legal foundation.