- Dutch companies must comply with both EU regulations and the Dutch Sanctions Act 1977, which imposes strict criminal and administrative penalties for violations.

- An Internal Compliance Program (ICP) is the primary legal defense for demonstrating due diligence to Dutch authorities during an audit or investigation.

- Dual-use goods require specific licenses issued by the Central Import and Export Office (CDIU) before they can leave the Port of Rotterdam or Schiphol Airport.

- Identifying Ultimate Beneficial Owners (UBOs) is mandatory, as sanctions apply not just to entities but to any person owning or controlling more than 25% of a business.

- Contractual "No-Russia" clauses are now a legal requirement for certain categories of sensitive exports under EU law to prevent circumvention via third countries.

How do Dutch firms implement an Internal Compliance Program (ICP)?

An Internal Compliance Program (ICP) is a structured set of internal policies and procedures designed to ensure a company complies with export control laws and sanctions. In the Netherlands, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs views a robust ICP as essential evidence of a company's commitment to "due diligence" and "duty of care."

A standard ICP for a Dutch trading firm should include the following core pillars:

- Management Commitment: A formal statement from the board of directors prioritizing compliance over commercial profit, ensuring that staff have the authority to stop suspicious shipments.

- Risk Assessment: A documented evaluation of the company's specific risks based on product type, geographic reach, and the nature of the customer base.

- Screening Protocols: Automated and manual checks of all parties (customers, suppliers, and financial intermediaries) against the EU Consolidated Financial Sanctions List.

- Training and Awareness: Regular workshops for sales, logistics, and legal teams to recognize "red flags," such as a customer's lack of familiarity with a product's technical characteristics.

- Record-Keeping: Maintaining detailed logs of all transactions and screening results for at least seven years, as required under Dutch administrative law.

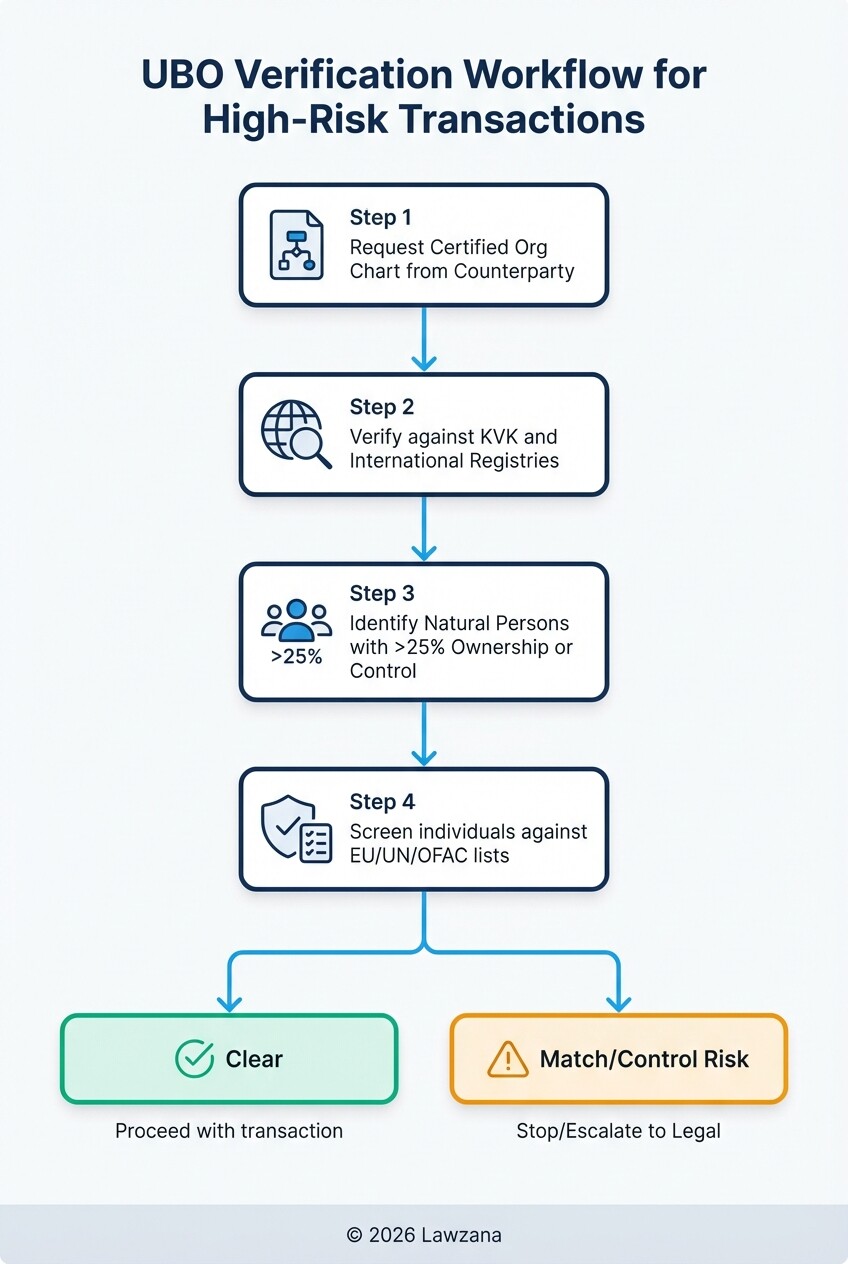

How is Ultimate Beneficial Ownership (UBO) verified in high-risk jurisdictions?

Verifying a UBO involves identifying the natural persons who ultimately own or control more than 25% of a legal entity or exercise significant influence over its operations. Dutch companies are legally prohibited from engaging in transactions that indirectly benefit individuals on a sanctions list, even if the primary entity they are dealing with is not listed.

To properly identify UBOs in high-risk jurisdictions, firms should follow these steps:

- Request Organizational Charts: Require the counterparty to provide a certified structure of their ownership hierarchy down to the natural person level.

- Consult Local Registries: While many jurisdictions have UBO registries, their reliability varies; use the Dutch KVK UBO-register as a baseline for domestic partners and reputable international databases for foreign ones.

- Cross-Reference Sanctions Lists: Use the names of identified owners to screen against EU, UN, and OFAC (U.S.) lists to ensure no "blocked person" holds a significant interest.

- Identify "Control" Mechanisms: Look beyond ownership percentages to see if a sanctioned individual has the power to appoint board members or direct the company's financial decisions.

What is the procedure for dual-use goods licensing in the Netherlands?

The procedure for dual-use goods licensing requires a formal application to the Central Import and Export Office (CDIU), which is part of the Dutch Customs authority. Dual-use goods are items, software, or technology that can be used for both civilian and military purposes, and their export is governed by EU Regulation 2021/821.

Exporters in the Netherlands must navigate these licensing categories:

- Individual Export Licenses: Required for a single shipment to one specific end-user. These require a detailed End-User Statement (EUS) to verify the final destination.

- Global Export Licenses: Valid for multiple shipments of specific goods to various countries or end-users, typically granted to companies with an established ICP.

- General Export Authorizations (EU GEAs): Pre-authorized licenses for specific low-risk destinations and goods, provided the exporter registers with the CDIU first.

The CDIU evaluation process typically takes 8 to 12 weeks. During this time, they assess the sensitivity of the destination country, the risk of diversion to a military end-use, and the technical specifications of the product.

| License Type | Scope | Processing Time |

|---|---|---|

| Individual | One exporter, one end-user | 8-12 weeks |

| Global | One exporter, multiple end-users | 3-6 months |

| General (EU GEA) | Pre-defined goods and countries | Immediate (after registration) |

Why are "No-Russia" and "No-Belarus" clauses mandatory for Dutch exporters?

"No-Russia" and "No-Belarus" clauses are mandatory contractual provisions that prohibit the re-export of specific sensitive goods to those territories. Under Article 12g of EU Regulation 833/2014, Dutch exporters must ensure that their contracts with third-country buyers (outside the EU and partner countries) contain these restrictions to prevent the circumvention of trade sanctions.

These clauses must include the following elements to be legally effective:

- Strict Prohibition: A clear statement that the buyer shall not sell, export, or re-export the goods to Russia or Belarus, or for use in those countries.

- Monitoring Mechanisms: The right for the Dutch exporter to request proof of the final destination or end-user from the buyer at any time.

- Immediate Termination: A provision allowing the Dutch company to terminate the contract immediately without penalty if the buyer violates the re-export restriction.

- Reporting Requirements: An obligation for the buyer to notify the Dutch exporter of any third-party attempts to circumvent the sanctions.

Failure to include these clauses in contracts involving high-priority battlefield items or aviation technology is a direct violation of EU law, regardless of whether the goods actually reach Russia.

How can companies mitigate civil and criminal liability for sanctions violations?

Mitigating liability in the Netherlands requires a proactive demonstration of "due diligence" to prove that the company did not intentionally or negligently facilitate a sanctioned transaction. Violations of the Sanctions Act 1977 and the Economic Offenses Act (WED) carry severe penalties, including prison sentences of up to six years and fines of nearly €1,000,000 per violation.

To minimize legal exposure, Dutch firms should implement these strategies:

- Voluntary Self-Disclosure: If a violation is discovered internally, disclosing it to the Dutch authorities (CDIU or the Fiscal Intelligence and Investigation Service - FIOD) before they find it can lead to significantly reduced penalties.

- Transaction Monitoring: Use real-time screening software that updates daily to reflect changes in EU sanctions lists, ensuring that a partner who was "clean" on Monday is not "blocked" by Wednesday.

- In-Depth End-User Verification: Go beyond paper declarations. Use third-party investigators or local embassy resources to confirm that the recipient's business premises and operations match their declared purpose.

- Contractual Indemnification: Ensure all trade contracts include strong indemnification clauses that hold the buyer liable for any legal costs or fines incurred by the Dutch exporter due to the buyer's breach of sanctions laws.

Common Misconceptions

"Our products are purely for civilian use, so export controls don't apply."

This is a dangerous misunderstanding of "dual-use" definitions. Many standard industrial items, such as certain high-performance valves, chemicals, or electronics, are classified as dual-use because they could potentially be integrated into military systems. Always check the Annex I list of EU Regulation 2021/821.

"We only need to screen the company we are selling to directly."

The EU "ownership and control" principle means you are also liable if you sell to a non-sanctioned company that is owned more than 50% by a sanctioned person or entity. Indirectly making funds or resources available to a sanctioned individual is a criminal offense in the Netherlands.

"Sanctions only apply to the physical shipment of goods."

Sanctions also cover "technical assistance," "brokering services," and "financial assistance." Providing repair instructions over email or facilitating a deal between two foreign entities can constitute a violation if the goods or parties involved are restricted.

FAQ

Which Dutch authority is responsible for enforcing sanctions?

The primary enforcement bodies are the Central Import and Export Office (CDIU) for licensing and the Fiscal Intelligence and Investigation Service (FIOD) for criminal investigations into sanctions evasion.

Can a Dutch company be fined if a customer re-exports goods to Russia without their knowledge?

Yes, if the Dutch company failed to perform adequate due diligence or failed to include the mandatory "No-Russia" clause. The company must prove it took all reasonable steps to prevent the diversion.

Is software considered a "good" under Dutch export control laws?

Yes. The transfer of software or technology via electronic media (email, cloud downloads, or even verbal technical support) is subject to the same export control regulations as physical hardware.

What are the "high-priority battlefield items" mentioned in EU regulations?

These are specific electronic components, integrated circuits, and sensors identified by the EU as critical to Russian military systems. These items are subject to the strictest export bans and "No-Russia" clause requirements.

When to Hire a Lawyer

Navigating the Dutch and EU regulatory landscape requires specialized legal expertise when:

- You are establishing an Internal Compliance Program for the first time and need it to pass a CDIU audit.

- You have discovered a potential violation within your supply chain and need to manage a voluntary self-disclosure to the FIOD.

- You are dealing with "dual-use" goods that fall into ambiguous technical categories.

- You are involved in complex M&A where the target company has significant operations in high-risk jurisdictions.

- You receive an inquiry or a formal notice of investigation from Dutch Customs or the Public Prosecution Service (Openbaar Ministerie).

Next Steps

- Audit your current database: Screen all active customers and suppliers against the most recent EU Consolidated Financial Sanctions List.

- Review your contracts: Ensure every international sales agreement includes a "No-Russia/No-Belarus" clause and a right-to-audit provision.

- Classify your products: Cross-reference your product catalog against the EU Dual-Use list and the Common Military List.

- Draft an ICP: If you do not have a written compliance policy, begin drafting one that outlines your screening and reporting procedures.

- Consult with a specialist: Reach out to a Dutch trade lawyer to review your compliance framework and ensure it meets the 2026 standards of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.