- Joint Ventures in India are primarily governed by the Indian Contract Act (1872), the Companies Act (2013), and the Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA).

- Enforcing non-compete clauses is legally challenging in India; they are generally only valid for the duration of the partnership and rarely enforceable post-exit.

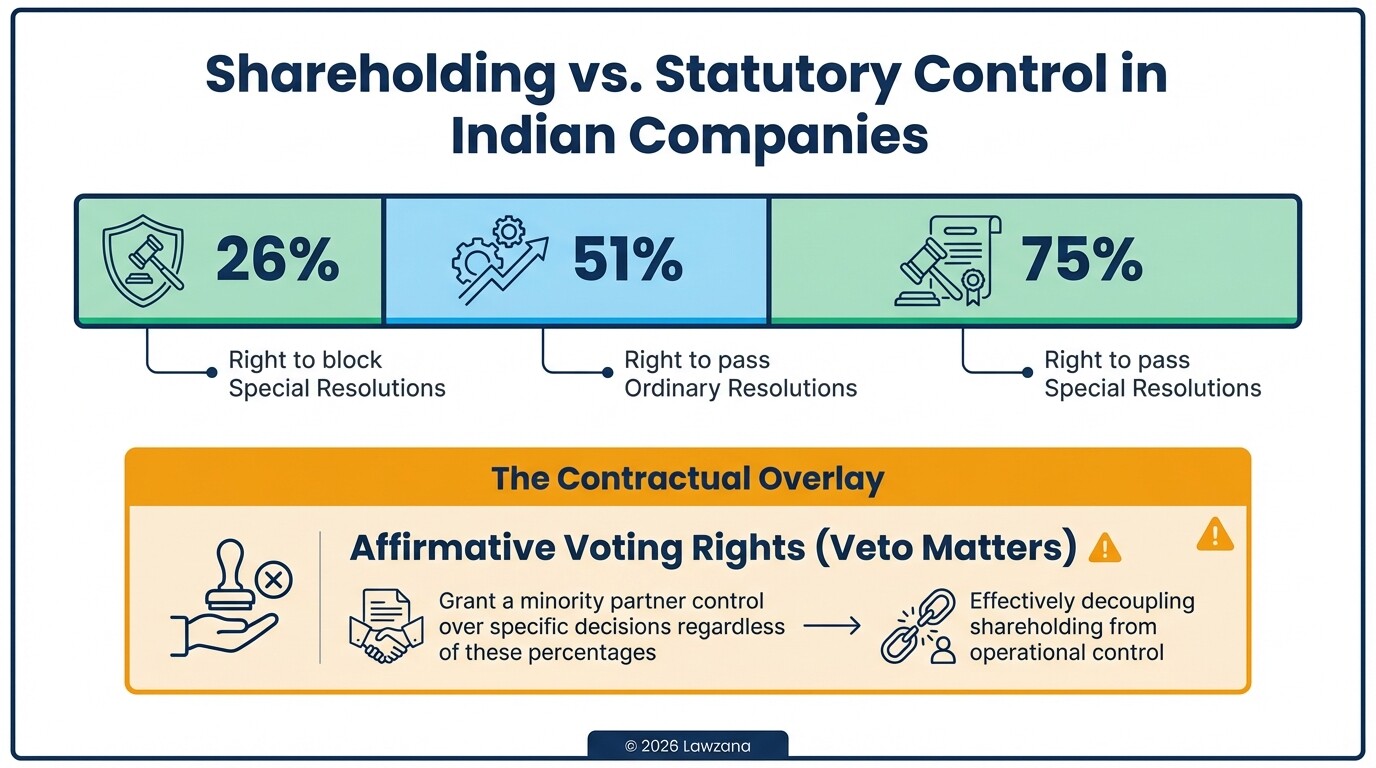

- Foreign partners should secure "Affirmative Voting Rights" (veto powers) over critical business decisions, regardless of their shareholding percentage.

- Choosing an international seat for arbitration, such as Singapore or London, is often preferred by foreign investors to ensure a more predictable legal process.

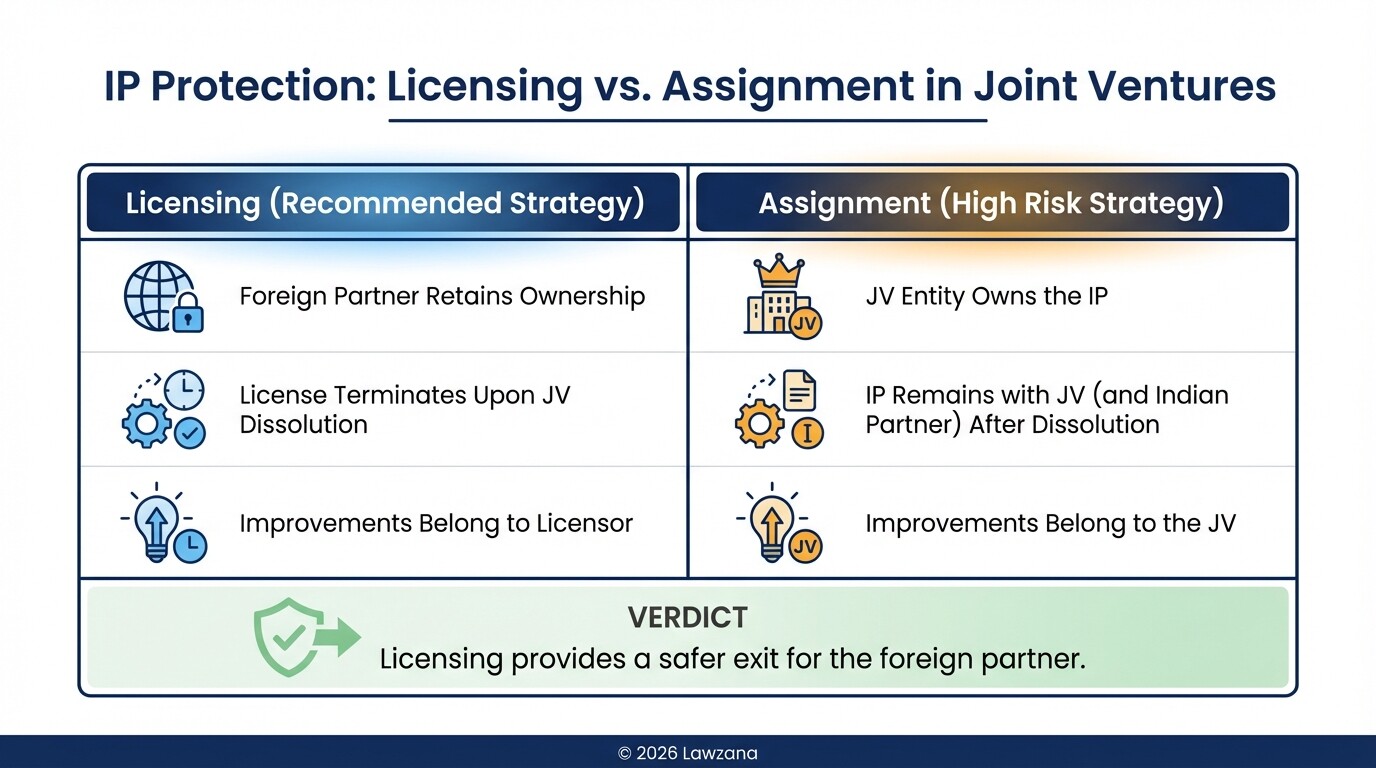

- Intellectual Property (IP) should be licensed to the JV rather than assigned, ensuring the foreign partner retains ownership if the partnership dissolves.

Joint Venture Drafting Checklist for Foreign Investors

To ensure a secure entry into the Indian market, foreign partners must address specific operational and legal risks during the drafting phase. This checklist focuses on the essential components of a robust Indian Joint Venture Agreement (JVA).

Essential Drafting Components

- Entity Structure: Determine if the JV will be a New Company (Equity JV) or a Contractual JV (Unincorporated). Most foreign investors prefer a Limited Liability Company under the Companies Act, 2013.

- Capital Contribution: Clearly define the cash and non-cash contributions (machinery, IP, technical know-how) and their valuation in Indian Rupees (INR).

- Condition Precedents: List all regulatory approvals required from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) or the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT) before the agreement becomes effective.

- Management Structure: Detail the composition of the Board of Directors, ensuring the foreign partner has the right to appoint a proportionate number of directors.

- Deadlock Provisions: Include "Buy-Sell" or "Mexican Standoff" clauses to resolve situations where shareholders cannot agree on critical decisions.

- Indemnification: Draft broad indemnity clauses to protect the foreign partner against pre-existing liabilities of the Indian partner or breaches of local compliance.

Sample Clause: Affirmative Voting Rights (Veto Matters)

"Notwithstanding anything contained in this Agreement, no action shall be taken by the Company, and no resolution of the Board or Shareholders shall be passed, in respect of the following Reserved Matters without the prior written consent of the Foreign Partner:

- Any amendment to the Articles of Association or Memorandum of Association.

- The issuance of new shares or any change in the capital structure.

- The incurrence of any debt exceeding ₹[Insert Amount] outside the approved Annual Business Plan.

- The appointment or removal of Key Managerial Personnel (KMP) including the CEO or CFO.

- Any transaction with a Related Party of the Indian Partner."

Drafting Enforceable Non-Compete and Non-Solicitation Clauses

Non-compete clauses in India are strictly scrutinized under Section 27 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, which declares any agreement in restraint of trade as void. For a foreign partner, this means a non-compete is generally enforceable only while the partnership is active.

To maximize protection, the JVA should define the "scope of business" narrowly and link the non-compete to the protection of trade secrets or goodwill. While post-termination non-compete clauses are usually unenforceable in Indian courts, non-solicitation clauses (preventing the Indian partner from hiring JV employees) are more likely to be upheld if they are reasonable in duration and geographic scope. Foreign partners should focus on "Gardening Leave" provisions or specific confidentiality agreements to bridge the gap left by the lack of post-contractual non-competes.

Defining Control and Governance Rights in Minority vs. Majority Stakes

Control in an Indian JV is not determined solely by shareholding percentage but by the rights negotiated within the Shareholders' Agreement (SHA). In India, a "Special Resolution" requires 75% approval, meaning a foreign partner with more than 25% can block major corporate changes.

If the foreign partner holds a minority stake, they must negotiate "Affirmative Voting Rights" over "Reserved Matters" to prevent the majority partner from making unilateral decisions on budgeting, mergers, or asset sales. For majority stakeholders, governance focus should be on "Quorum" requirements, ensuring that no board meeting can be validly held without the presence of their nominee director. It is vital to incorporate these contractual rights into the company's Articles of Association (AoA) to make them enforceable against the company under the Companies Act, 2013.

IP Protection Strategies for Technology Transfer to Indian Partners

Intellectual Property is often the most valuable asset a foreign partner brings to an Indian JV, making it the most vulnerable to misappropriation. In India, it is legally safer to license IP to the JV entity for a specific term rather than transferring ownership (assignment).

A robust Technology Transfer Agreement should clearly define "Background IP" (owned by the foreign partner) and "Foreground IP" (developed by the JV). The agreement should explicitly state that any improvements made to the technology during the JV term belong to the foreign partner. Furthermore, ensure that the license automatically terminates upon the dissolution of the JV or a change in control of the Indian partner, requiring the immediate return or destruction of all technical documentation and proprietary data.

Dispute Resolution Mechanisms: Choosing Between Indian or International Seats

Dispute resolution in India can be time-consuming, leading most foreign investors to prefer institutional arbitration over litigation in Indian courts. The "Seat" of arbitration is the most critical choice, as it determines which country's laws govern the arbitration process and which courts have supervisory jurisdiction.

While India's Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 has been amended to be more pro-arbitration, many foreign partners still opt for an international seat like Singapore (SIAC) or London (LCIA). This provides a neutral ground and often leads to faster resolution. However, if the JV's assets are entirely in India, the foreign partner must ensure the agreement allows for "Interim Relief" from Indian courts (under Section 9 of the Act) to freeze assets or protect IP while the international arbitration is pending.

Pre-emption Rights and Clear Exit Triggers for Foreign Investors

An exit strategy must be baked into the JV agreement from day one to prevent the foreign partner from being "trapped" in a failing or stagnant partnership. Pre-emption rights, such as the Right of First Refusal (ROFR) and Right of First Offer (ROFO), dictate how shares can be sold to third parties.

Clear exit triggers should include:

- Material Breach: A significant violation of the JVA terms by the Indian partner.

- Change in Control: If the Indian partner's company is acquired by a competitor of the foreign partner.

- Deadlock: If the partners cannot agree on the annual budget for two consecutive years.

- Put/Call Options: These allow the foreign partner to either force the Indian partner to buy their shares (Put) or force the Indian partner to sell their shares (Call) at a pre-determined valuation formula, subject to RBI pricing guidelines under FEMA.

Common Misconceptions

"A signed contract is immediately enforceable in India."

In reality, many clauses in a JVA, particularly those involving the transfer of funds or shares, are subject to mandatory regulatory approvals from the RBI or the Income Tax Department. A contract that violates FEMA pricing guidelines is unenforceable regardless of what the partners signed.

"If I own 51% of the shares, I have total control."

Ownership does not equal operational control in India if the minority partner has negotiated strong veto rights or "Affirmative Vote" clauses. Without a carefully drafted Articles of Association, a majority owner may find themselves unable to pass even basic resolutions.

"Non-compete clauses protect me after the JV ends."

This is a frequent mistake. Indian courts view post-termination non-competes as a violation of the fundamental right to livelihood. Foreign partners often rely on these clauses only to find them struck down during litigation.

FAQ

What is the difference between a Shareholders' Agreement (SHA) and a JV Agreement (JVA)?

A JVA is the overarching agreement to cooperate, while the SHA focuses specifically on the rights, duties, and obligations of the shareholders, including board seats, dividends, and exit rights. In practice, these are often combined into one document.

Can a foreign partner be the Managing Director of an Indian JV?

Yes, a foreign national can be appointed as a Managing Director, provided they comply with the residency requirements and obtaining a Director Identification Number (DIN) under the Companies Act, 2013.

Is electronic signing valid for JV agreements in India?

Yes, under the Information Technology Act, 2000, e-signatures are legally valid. However, for documents requiring physical "stamping" (payment of stamp duty), physical execution is still the standard practice to ensure the document is admissible in court.

How much does it cost to register a JV company in India?

The government filing fees for incorporating a company are relatively low (often under ₹50,000 for standard capital), but the "Stamp Duty" on the JVA and SHA varies significantly by state (e.g., Maharashtra vs. Delhi) and is based on the capital involved.

When to Hire a Lawyer

Navigating the Indian regulatory landscape requires professional legal counsel at several stages. You should hire an Indian corporate lawyer if:

- You are entering a sector with "Press Note" restrictions or FDI caps (e.g., Defense, Print Media, or Multi-brand Retail).

- You need to conduct "Legal Due Diligence" on a prospective Indian partner's existing liabilities and litigation history.

- You are drafting the Articles of Association (AoA) to ensure they mirror the protections in your JVA.

- You require a formal "Legal Opinion" for your home country's board regarding the enforceability of exit options under FEMA.

Next Steps

- Due Diligence: Conduct a comprehensive background check on the Indian partner's financial health and local reputation.

- Term Sheet: Draft a non-binding Term Sheet to align on core principles like valuation, governance, and exit triggers before moving to the full JVA.

- Regulatory Check: Verify the current FDI policy for your specific industry to ensure the proposed shareholding structure is legal.

- Local Counsel: Retain a law firm in India to handle the stamping and registration requirements to ensure the agreement is fully admissible in Indian courts.